Sirens torment Ulysses with their enchanting song in Herbert James Draper’s 1909 painting titled ‘Ulysses and the Sirens.’ Draper portrays the Sirens as sexualized mermaids, consistent with other Edwardian era depictions of the creatures.

© Ferens Art Gallery / Bridgeman Images

For thousands of years sirens have lured sailors, haunted coastlines—and shapeshifted through myth and media. Here’s how they evolved to the seductive mermaids of our modern imagination.

The Greek hero Odysseus famously faces many travails as he attempts to return home following the Trojan War, from giant cannibals to enigmatic enchantresses. But one challenge stands out as perhaps the most evocative, dangerous, and enduring of them all: the sirens, with their hypnotic and mesmerizing song, who call to passing sailors. To stop is certain death.

They’re powerful and mysterious figures and even now, of all the creatures from Greek myths, audiences simply can’t get enough of them.

Sirens have been a fixture of the Western imagination since the time of Homer and the composition of The Odyssey in the 8th century B.C. They appear in the works of ancient Roman writers like Pliny the Elder and Ovid, and one even appears in Dante’s Divine Comedy. They fascinated painters of the 19th century and now lend their name to television shows and the “siren-core” fashion aesthetic touted by social media creators.

(Dante’s ‘Inferno’ is a journey to hell and back.)

But these mythological creatures have shifted forms dramatically over the centuries, transforming with the times to reflect society’s complicated and ever-changing relationship with desire. In modern popular culture, sirens are alluring creatures of the sea, most commonly women, often sporting shimmering mermaid tails. But their ancient Greek roots weren’t fishlike at all; instead, they were bird-bodied creatures associated with death.

Here’s how sirens have evolved over time, and why their song stays so loud in popular culture.

A attic terracotta status from Greece 300 BCE shows Sirens in their original, bird-woman form.

Photograph by Peter Horree, Alamy Stock Photo

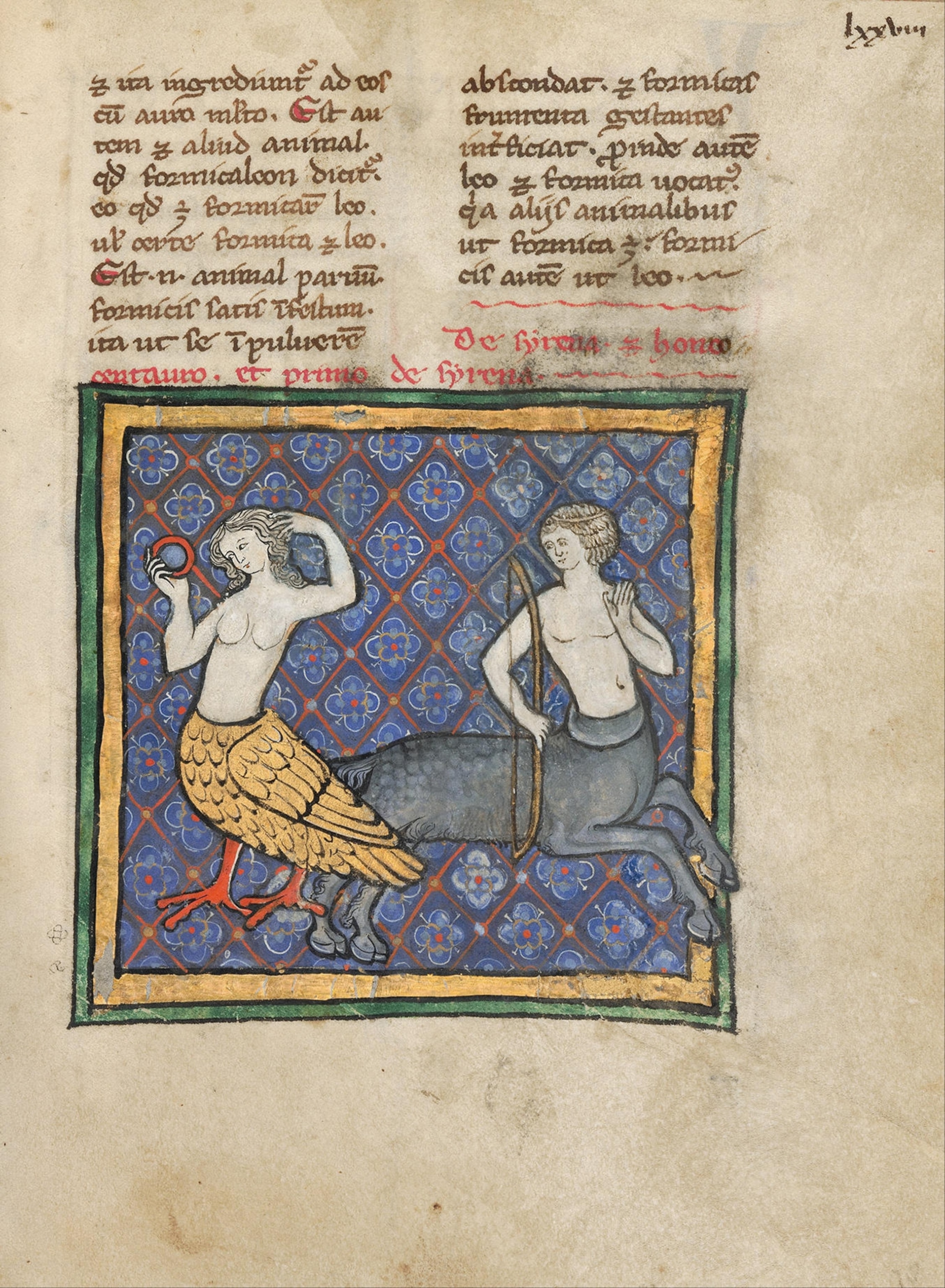

This artwork titled ‘A Siren and a Centaur’ shows how classical mythology and artistic imagination have blended together to reshape Sirens iconography. The piece portrays a bird-like siren (left) and centaur (right) in an imaginative and dynamic scene.

Photograph by ART Collection, Alamy Stock Photo

What are sirens?

Homer’s Odyssey is the sirens’ earliest appearance. Thought to have been composed sometime in the 8th century B.C., the poem follows the winding path of the hero Odysseus as he returns home to Ithaca and his long-suffering wife from the Trojan War. Along the way, he faces Greek gods, marvels, and monsters, including the sirens.

The sorceress Circe warns him about the creatures, telling him that they “bewitch all passersby. If anyone goes near them in ignorance, and listens to their voices, that man will never travel to his home.”

Odysseus plugs his men’s ears with wax, so they won’t be lured—but he leaves his own ears free and commands his men to bind him to the ship’s mast, so he’s able to hear their promises as they tempt him with the prospect of knowledge and tales of heroic deeds.

(The Odyssey offers monsters and magic—and also a real look into the ancient world.)

But the Odyssey is far from the only story featuring the sirens. They also appear in the Argonautica, a 3rd century B.C. epic poem following Jason and the Argonauts in their search for the Golden Fleece, where sirens are described as daughters of the river god Achelous and the muse Terpsichore. The musician Orpheus snatches up his lyre to drown out their song—but not before one member of the crew throws himself in the ocean. Tradition has it that the names of those sirens were Parthenop, Ligeia and Leucosia.

Perhaps the siren’s most important distinguishing feature—and the one that remains to this day—is their voice. “It’s a hypnotic voice, it lures people, makes them forget everything, in a lot of cases makes them fall asleep,” says Marie-Claire Beaulieu, associate professor of classical studies at Tufts University. “Essentially, people become so hypnotized that they forget everything.”

What do sirens symbolize in Greek culture?

“When the ancients say sirens, they mean a bird-bodied woman,” says Beaulieu.

Closely associated with death, sirens’ bird legs and wings show that they’re liminal creatures who dwell betwixt and between. Their connection with the sea, which the ancient Greeks considered profoundly dangerous, and their wings, situate them somewhere between earth and air.

Sirens were a fixture of ancient Greek funerary art, such as stele, a type of grave marker. For example, Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts holds a funerary plaque from the 7th century B.C. depicting a mourning scene, in which two women flank a funeral couch that holds a corpse. Crouched underneath is a siren.

You May Also Like

Some sources, including Euripides’ 5th century B.C. play Helen and Ovid’s 8th century A.D. poem Metamorphoses, associate the sirens with Persephone, the goddess of spring carried off by Hades, god of the underworld, to become his queen. Some stories say they were given wings to seek Persephone. According to Beaulieu, some sources, including the Argonautica, show sirens as the daughters of one of the Muses. “Except that in a way, they’re the Muses of death, instead of the Muses of life, because they lure people to death with this singing,” says Beaulieu.

This mural from the 14th century shows a Siren playing music. During this period, the enchantresses were depicted as both bird-women and mermaids.

Photograph by Heritage Image Partnership Ltd, Alamy Stock Photo

How the iconography of sirens has evolved

Sirens retained their bird bodies into the time of the Roman Empire and well beyond; Pliny the Elder includes them in the “Fabulous Birds” section of his Natural History, written around A.D. 77, claiming they lull men to sleep with their song and then tear them to pieces. (Though he’s a skeptic that they exist.)

But over the course of the Middle Ages, the siren transformed. More and more they began exhibiting fishtails, not bird bodies. The two types coexisted from the 12th through 14th centuries at least, Beaulieu explains, but eventually the mermaid-like creature emerged as dominant.

That shift is probably thanks in part to the strong Greek and Roman tradition of unrelated sea gods like Triton, as well as the sirens’ association with water. But it’s also thanks in no small part to the influence of Celtic folklore traditions.

“The blending is a super interesting syncretism of cultures,” says Beaulieu, pointing to 14th century tradition about St. Brendan the Navigator, an early Irish Christian whose journeys parallel those of Odysseus. Naturally, he encounters a siren on his odyssey—only this one is wholly recognizable to modern audiences as a mermaid.

How Christianity has shaped Greek mythology

As the physical appearance of the sirens began to shift, so did their symbolic meaning.

The sirens of ancient Greece were considered beautiful—but they tempted Odysseus with songs of glory, not simply sex. Ancient Greeks were more concerned with power dynamics, so a man having sex with a subordinate woman wasn’t a problem. “You get into trouble when you have a goddess having sex with a mortal, for instance,” explains Beaulieu. “That’s part of what would have given the sirens their menace.”

But medieval Christianity saw sex and sirens differently. They became symbols of temptation itself, a way to talk about the lures of worldly pleasures and the deceptive, corrupting pull of sin. Hence the appearance of a siren in Dante’s 14th century Divine Comedy. The very same creature who tempted Odysseus comes to Dante in a dream and identifies herself as “the pleasing siren, who in midsea leads mariners astray.” In the end, his guide and companion through the underworld (the epic poet Virgil) grabs her, tears her clothing, and exposes the “stench” of her belly showing the medieval siren is sexually alluring but repulsive.

Those medieval temptresses are unmistakably the roots of modern sirens, with their dangerously attractive songs. The association between sirens, mermaids, and temptation only grew tighter in the 19th century, when painters returned again and again to creamy-skinned, bare-breasted sirens with lavish hair. There is no better example than John William Waterhouse’s turn-of-the-century painting The Siren, where a lovely young woman gazes down at a stricken, shipwrecked young sailor who looks both terrified and enthralled.

The sirens of modern-day popular culture

Millennia later, the sirens continue to resonate. They’re even inspiration for a fashion aesthetic: sirencore, a beachy and romantic look with just a little hint of menace.

Modern creatives, meanwhile, are still turning to the sirens as a source of inspiration and a rich symbol for exploring power, gender, and knowledge. Netflix’s new release Sirens, which adapts Molly Smith Metzler’s 2011 play Elemeno Pea and stars Julianne Moore, explicitly grapples with the mythological figure. Director Nicole Kassell told The Hollywood Reporter, “I love the idea of analyzing the idea of what a siren is, and who says what a siren is—the sailor. It’s very fun to get to go back and consider it from a female lens.” Black sirens navigate the challenges of modern-day sexism and racism in Bethany C. Morrow’s 2020 A Song Below Water; a Puerto Rican immigrant falls in love with a merman on turn-of-the-century Coney Island in Venessa Vida Kelley’s 2025 When The Tides Held The Moon.

For many writers, sirens are an opportunity to turn old tales and stereotypes on their head, using characters who’ve long been reviled and distrusted for their controversial power. The Sirens by Emilia Hart is one such modern-day retelling, which weaves between the modern day, and the 19th century transportation of Irish women convicts to Australia.

“I thought this mythological creature was the perfect way to give my female characters some power back into this historical narrative,” she explains. “I wanted to make this general comment on how we think about women and how we have this idea of women as being temptresses, and we demonize them and we overly sexualize them, as a way of trying to explain or perhaps diminish their power,” she says.

In the hands of modern-day writers, the sea can become a place of transformation, freedom, and potential. And sirens can be restored to a place of power and wisdom—and, yes, a bit of danger too.